“Have Australians, today, the ‘will to do great things together again’?”

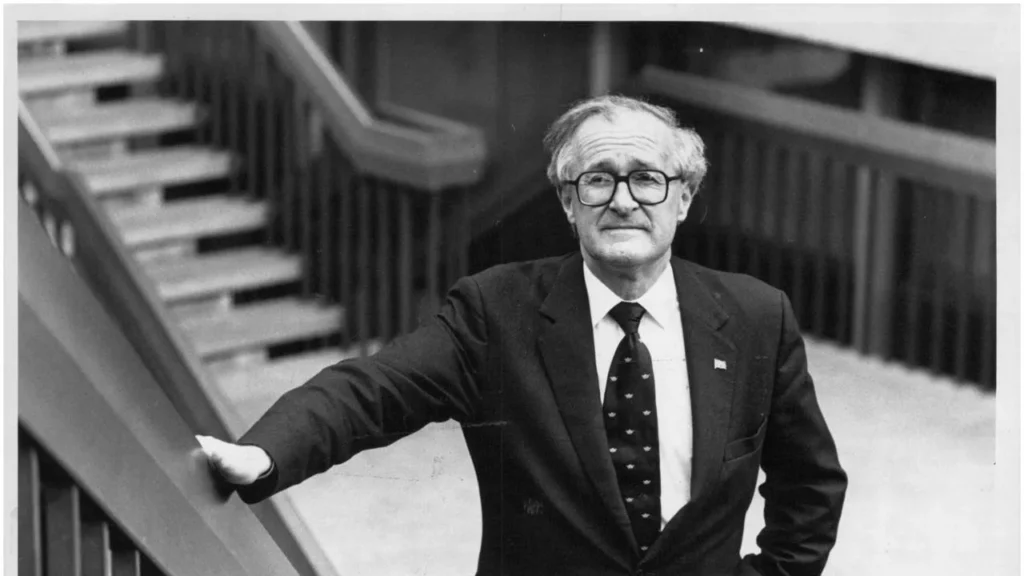

The previous three articles in this series have profiled the three founding members of the dries, John Hyde, Peter Shack, and Jim Carlton. Once the three got together and got a bit more organised, their intellectual and political movement picked up some fellow travellers in the public sector, the private sector, and the universities. One of their most important intellectual colleagues in the public service was John Stone.

Stone was born on 31 January 1929, in Perth, to his wheat farmer father and schoolteacher mother. After school at Perth Modern, Stone studied at the University of Western Australia and then as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford.1 After graduating from Oxford in 1954, Stone took up a position with the Commonwealth Treasury where he worked for almost all of the next 30 years before he resigned to criticise the Hawke government.

During his years at Treasury, Stone rose through the ranks and became one of the key players in the broader ‘dry’ movement, lending support to parliamentarians who wanted to see Australia unburden itself from the economically restrictive policies of the past. As the Institute of Public Affairs’s Morgan Begg has written: “While the 1980s are remembered for the influence of Hawke and Keating, it was John Stone and his allies, such as businessmen Ray Evans and Hugh Morgan, who were shifting the dial on market-based economic reform.”

Stone became the Treasury Secretary in 1979, but even before this, as Deputy Secretary, his intellectual heft was felt. The year prior, journalist Paul Kelly referred to Stone as “one of the two men who ran the nation”, the other one being Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. Stone was ideologically aligned with the Fraser government, or at least with what the Fraser government could have been.2 As it became clear that Fraser was not going to live up to the expectations the dries and other economic rationalists had in mind, Stone was glad to have the dries in parliament publicly saying some of the things he and Treasury were warning the government of about Australia’s wayward path. Stone later said that the dries “ were putting a big stick around in the otherwise bloody hopeless ranks of the Coalition. Treasury was pretty glad to see them.”

When the Fraser government was elected in 1975, it inherited a number of challenges from the Whitlam Labor government. Robert Menzies had left the Lodge in 1966 with annual inflation at 2.7%. When Whitlam came to power in 1972 it was 6.8%, but he quickly increased it to 16.7%. When Fraser came to power there emerged a group arguing to ‘fight inflation first’, which was the view promoted strongly by Stone at Treasury. As recalled by David Kemp, who was a member of the Fraser team:

The need to reduce expenditure sharply was also the view of the Treasury, although Fraser and Treasury came to differ on the scale and the speed with which spending should be cut and on the balance to be struck between tax restraint and reducing the deficit… The key protagonist of the official view on budgetary policy was Treasury’s rising star John Stone, whose brilliant mind, acerbic tongue and deeply held values were accompanies by a determination to win the policy debates that was a match for the Prime Minister’s. Stone was the most brilliant economic policy analyst and advocate within the Treasury and, indeed, the public service. He passionately pursued a self-appointed mission to rescue Australia from the policy errors undermining national prosperity that had accumulated over decades and that he believed had reached their extreme expression under Whitlam. It was a mission he would pursue at first from within the public service and later as a brave and forceful public voice and a senator.3

Stone announced that he would retire from the public service and his position as Secretary of the Treasury on 15 August 1984. He wanted to more publicly criticise the Hawke government and centralised wage fixation, which Treasury believed was a significant cause of unemployment, and which Stone argued was “a crime against society”. His opportunity came while he was still the Secretary on 27 August when he delivered the Edward Shann Memorial Oration, named after the Australian economist who had fiercely criticised centralised government in the 1930s.4

In his address, titled “1929 and All That………”, Stone drew parallels between the 1920s and the early 1980s, in which he saw the same “financial mismanagement, protectionism and ossified labour markets”. “In this lecture I shall point out that, although history rarely repeats itself precisely,” Stone said, “there are again some ominous signs of economic disjointedness today both in Australia and in that wider world in which, whether we like it or not, we still have to find our own economic salvation.”

Stone was scathing of the end of the Fraser government and the beginning of the Hawke government for throwing away “all that ground so painfully won back over the previous seven years” when it came to the federal Budget. He highlighted the damage of “mindless micro-economic episodes” inflicted on Australia “by a few particular greedy and ignorant trade union leaders, abetted in some degree by some of their business counterparts and, not least, by the arbitral tribunals.”

The fact is that there has been in Australia an unwillingness to view the workings of labour markets like other markets – in terms of supply, demand and price. Yet employment, unemployment and wages – the things which do attract attention and concern – are nothing more than the labour market reflections of the operation of supply, demand and price.

…

It is… one thing to say that market behaviour is not recognised in the case of labour markets; it is quite another thing to say that supply, demand and price effects do not operate in labour markets.

Of course, they do; and the chief effect of the cartloads of regulatory manure which have been spread upon those labour market fields has been to produce a great flourishing of weeds while retarding the growth of the crop of jobs which those fields might otherwise furnish.

After he liberated himself from the public service, Stone became a prolific advocate for dry reforms, especially for making the labour market more flexible and fixing the chronic issue of youth unemployment. The Shann lecture was just the start, where Stone laid out his philosophy and made the case that addressing issues in the labour market was critical to ensuring the future prosperity of Australians. In the following years, he would work as a senior fellow at the Institute of Public Affairs, write for Australian newspapers on this issue, and help establish the H.R. Nicholls society, a think tank which mounted the argument against centralised wage fixation and Australia’s sclerotic industrial relations system.

Stone also worked as an advisor to Queensland Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen and was offered the number two spot on the National Party’s Queensland senate ticket at the 1987 election, which sparked a short-lived career in the parliament, which ended in 1990 after a failed attempt at transferring to the House of Representatives.

In his 1984 lecture, Stone remarked that, looking around Australia one could see “at almost all points the spirit of enterprise is shackled and weighed down by the dead hands of government.”

He was a fan of looking to the past for lessons for the future. “Australians may gradually have allowed themselves to be put – or kept- in hobbles by unworthy men masquerading as leaders,” he noted, but without doubt about “the capacity of Australians to rise up and throw off those hobbles if they set their wills to doing so.”

“Australians have, in years past, ‘done great things’ – not only together but also individually,” Stone reminded his audience, posing a final question: “Have Australians, today, the ‘will to do great things together again’?”

1 The same schooling and university pathway of his contemporary and future Prime Minister, Bob Hawke.

2 Like the parliamentary dries, Stone was disappointed in the missed opportunity that was the Fraser government, later wondering: “How could Fraser leave office in 1983 with so little achieved in turning back the Whitlamite tide of destruction?”

3 David Kemp, Consent of the People, pp. 172-173.

4 Shann’s work remains insightful to this day. He concludes his famous An Economic History of Australia, first published in 1930, with this stinging critique of government price manipulation: “These schemes of price manipulation one and all bespeak a hazy appreciation of the function of prices in guiding the economic use of man’s resources. Australians have too often legislated as though a price might be made at whatever figure the producer in search of an easier life chose to call ‘the fair thing’. But the prices that direct the goings and comings of sound prosperity are the signs by which men learn from willing buyers their changing needs. High prices encourage production where it affords a margin of profit. Falling prices discourage it by wiping out the margin or hope of profit. A government or board of control that seeks to fake the world’s prices does so at the peril of the citizens and producers whom the faked prices mislead.”