“…lags are long and another generation’s fortunes turn upon what we do now.”

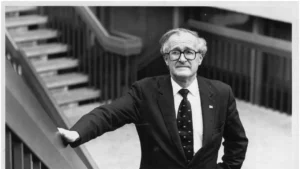

As Bert Kelly was nearing the end of his parliamentary career, a young, one-armed farmer from Western Australia joined him on the backbenches. John Hyde was born on 2 February 1936 in the Wheatbelt of Western Australia, where he grew up and started his career as a sheep and wheat farmer.

Like other Australian farmer-politicians, Hyde’s views on economic policies were driven early on by his experience living and working on the land. His father participated in the campaign against the Chifley Labor government’s attempt to nationalise the banks in 1947, handing out flyers in Dalwallinu, suggesting an early influence.

But it was once Hyde came to farming in his own right that his ‘dry’ instincts were solidified. As Hyde explained in a video for the Mannkal Foundation in 2014: “The wheat board taught me an awful lot about how not to manage an economy. I was busy delivering every wheat seed I could to the pool, I didn’t grow quality wheat, which I could’ve quite easily grown on my land type, because I wasn’t paid for it… I knew I could produce quality, but I wasn’t allowed to sell it, so I didn’t.”

Hyde had been a member of the Dalwallinu Shire Council from 1966 to 1971. It was after the farming accident in which he lost his arm that he ran for and won the seat of Moore in 1974, which he held through the duration of the Fraser government (elected the following year) until the Hawke government in 1983.

John Hyde later recalled one of his first interactions with Bert Kelly as a novice MP, after he had been asked by the Opposition Whip to “bucket” the Whitlam government in a speech, saying that “it was at Kelly’s feet that I learned enough for later Whips to ask me not to speak.” Kelly became Hyde’s personal hero and mentor, and passed on the baton he had taken over from those such as Charles Hawker (in parliament from 1929-1938) as one of the principle advocates for economic freedom and less trade protection and government interference.

Although he may have briefly played the “party political” game, Hyde’s political instincts were on display from his maiden speech given on 2 August 1974. Hyde said that he would be “hard pressed to find two people among the 64,000-odd constituents of Moore who have identical needs, abilities or ambitions” and that it was therefore “clearly ridiculous to imagine that one strong central government could cater for such diversity.”

“It is clearly ridiculous to imagine that a government 2,500 miles away can make itself aware of the ambitions of groups of parents at Girrawheen or Beacon or the new priorities for roads at Leeming or Kalamunda, or to understand the difficulties of new land farmers or the traffic in Wanneroo Road. It is even more ridiculous to imagine that a central government can rank all diverse matters in some meaningful priority and act in the best interests as seen by the local population.”

At the 1977 election, Hyde was joined in parliament by Peter Shack and Jim Carlton. The three quickly formed an informal coalition, working together to lobby the Fraser government to adopt a more liberal economic policy by dropping trade barriers and protectionist measures. As previously summarised:

Hyde, Shack, and Carlton came together to form the ‘dries’, meeting in Carlton’s office each parliamentary sitting day. As Shack recalled, the three would meet “over Carlton-supplied Chinese green morning tea… [to] exhaustively discuss and plan how we could encourage and influence the conservative Fraser government to move to adopting more market-based and competitive policies.”

The three were philosophically aligned around the liberal ideals set down by thinkers like Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, and Friedrich Hayek. They decided to take on the work of advocating for the policy changes they saw as being in the long-term interests of the Australian people.

In divvying up their areas of focus, Hyde took on the broad issues of budget reform, tariffs, and protectionism, honouring his mentor, Bert Kelly. Their efforts were directed at critiquing the government they were members of. In a speech given in May 1979 in response to his own government’s Budget, Hyde argued that the time was right to cease intervening with businesses and reduce industry protection and trade barriers. “The economy is now moving and now is the time to tackle the tariff problem,” he said:

Reshuffling the burdens might help some industry but it will always be at the expensive of others. Export Now programs, export incentives schemes, bounties, tariffs, preferential government purchasing and concessional lending arrangements are all paid for by others in the community… Industry desperately needs, above all else, for government to get off its back.

Hyde later wrote about the importance of the dries being well-organised. When they met each week before the Liberal party room meeting, Hyde, Shack and Carlton prepared their lines and their tactics for the specific issues of the day. “By not going into the party room unaware of the agenda, we could think about and discuss our reactions to Wet proposals,” Hyde wrote:

By not sitting together, we looked less like the minority rump hat we were. By not all rising together when an item was called on, we were able to counter what we believed was the Prime Minister’s tactic of calling his critics first and those most likely to rebut the criticism later. We vowed never to let each other be seen to lack support when attacked by Wets or ministers.

The dries’s arguments were based on a set of principles, rather than a fixed idea of what the Australian economy or society should look like. They wanted smaller, stronger government, a commitment to the rule of law and property rights, and the freedom for Australians to trade with each other and the world through a market economy with clear and equally applied rules without rent-seekers being able to benefit at the expense of the broader community.

As John Hyde himself summarised the mission in his book Dry: In Defence of Economic Freedom:

A capitalist economy will not deliver prosperity nor a society opportunity, security and justice unless basic institutional underpinnings are maintained. A captive or over-extended Government is not a strong one. The Government advocated by Dries would be more limited than that to which we are accustomed. Sticking to its essential protective functions, it would find it easier to adhere to principles that avoided ‘corruption’… It would be able to say ‘no’ to vested interests.

Concentrating on procedural justice it would not grant privileges such as industry protection. It would respect tried and proven institutions such as private property rights, independent courts, the parliament, the federal structure and families. It would offer Government welfare to those who are least able to provide for themselves but expect others to provide for themselves and their families. That is, it would combat absolute poverty. It would not intrude unduly upon people’s private domains. It would face inconvenient facts.

Dries may be identified by their efforts to bring impartiality to law making and administration by Governments and Parliaments that is comparable with the impartiality that the courts bring to the law’s interpretation. They, however, advocate a way not a destination.

Hyde’s parliamentary career ended at the 1983 election which saw the Hawke Labor government come to power. It was the Hawke government that first started to implement much of the dry policy agenda which the Liberals had failed to pursue. At the conclusion of his book, John Hyde outlined how these reforms took place and the organisation necessary to enable a similar wave of reform:

The Australian reforms of the 1980s and early 1990s had been part of a worldwide phenomenon. They had more followed than led the spirit of the times but neither the zeitgeist itself nor Australia’s ability to follow it had been chance. My personal hero, Bert Kelly, and many others had preached, nagged and recruited with the possibility of such reforms always in mind. If such a period of exceptional government is to be repeated, then leaders – politicians, think tanks, academics, and business and trade union officials – must cause it to be repeated.

Outside of parliament, Hyde continued to provide this leadership, writing newspaper columns in the style of Bert Kelly and his ‘Modest Member’ and ‘Modest Farmer’ columns. (The Mannkal Foundation has made many of these articles available through the John Hyde Archives which can be accessed here.) He established the Perth-based Australian Institute for Public Policy think tank, and ran it until it merged with the Institute of Public Affairs in 1991 (which he then ran for four years).

Hyde spent his entire parliamentary and post-parliamentary career advocating for the dry policies that proved incredibly effective at raising Australian living standards. As highlighted before, the work of the dries was done on a very long time horizon. It wasn’t until he left the parliament, after almost a decade of arguing for less protectionism and freer markets, that the policies he had advocated for started to be implemented.

Hyde’s final words of his book are worth repeating: “Political and economic lags are long and another generation’s fortunes turn upon what we do now.”