“… I found the ‘what should be’ far more exciting than the ‘what is’.”

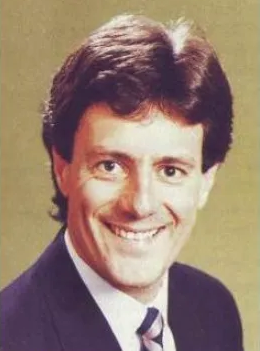

When he was first elected in 1977 at 24-years-old, Peter Shack was the youngest MP in the Australian parliament. Following in the long-established tradition of impressive young members elected with a thought-out political philosophy,1 Shack would quickly set out to help establish the dries, critique the Fraser government, and help set the stage for Australia’s wave of economic reform in the 1980s and 1990s.

Shack was born in Perth on 20 June 1953 into a small business family. His grandfather, Andrew Shack, had founded an automotive repair shop in Fremantle which his father and uncle later worked at. Between a short stint at a law degree and switching to a political science degree in the early 1970s, Shack worked for his father driving the spare parts delivery van around Perth.

The switch from law to a political degree was because, as Shack put it: “Law is about what is, politics is about what should be… and I found the ‘what should be’ far more exciting than the ‘what is’.”2 The 1975 federal election, when Malcolm Fraser led the Liberal-National coalition to what remains the largest majority government formed in Australia with 91 out of 127 seats, coincided with the end of Shack’s studies. He wrote to several newly elected Liberal MPs looking for a job and ended up working for the new member for Tangney, Dr Peter Richardson.

When Richardson decided not to contest the 1977 election for the Liberals, Shack put his hand up and won pre-selection against eight other candidates, and went on to win the seat. With a brief interruption between the 1983 and 1984 elections, Shack was the member for Tangney from 1977 until his political retirement, aged 39, at the 1993 election.

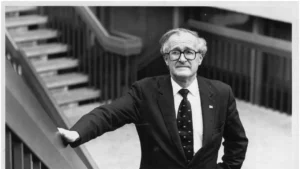

In early 1978, Malcolm Fraser ironically brought together two of the founding dries, Shack and the 42-year-old Jim Carlton (member for Mackellar from 1977 to 1994).3 “Despite our significant age geographic and age differences we were immediately thrown together when the Prime Minister’s Office asked Jim to move the address-in-reply motion to the governor-general’s speech… and me to second”, Shack later recalled. “Thereafter, bound by our readily apparent and shared political philosophy and views and consequent policy prescriptions, Jim and I remained close parliament and personal friends until our retirements 16 years later.”

In this maiden speech, delivered on 22 February 1978, Shack highlighted a number of the issues that would bind the dries together: “continued taxation relief – keeping money in the pockets of those who earn it, giving them the responsibility and the freedom to dispose of it as they wish and choose”, “giving the States and local government greater decision-making powers and responsibility – putting power where it belongs, closest to the people it most effects”, and the “urgent development of our uranium resources and the North West Shelf.”

John Hyde had been in the parliament for two years already, accepting the torch of economic liberalism passed onto him by Bert Kelly. When Shack and Carlton joined Hyde on the backbenches, the three decided to get together and organise themselves so that their philosophical alignment might be effectively deployed to “encourage and influence the conservative Fraser government to move to adopting more market-based and competitive policies.”

In the late 1970s there was much which needed to be done to drag Australia out of the protected mercantilism of the 1950s and 60s in order to ensure a more internationally competitive nation and greater prosperity for all its citizens. Bert Kelly had been ringing the bell for years on the adverse consequences of Australia’s high tariff regime. We knew we collectively had inherited that baton of responsibility but… that we needed some tactical and strategic success. We could not effectively take on all big targets, all at the same time.

Like Hyde and Carlton, Shack’s hopes for what the Fraser government could be were quickly let down. “We had such high expectations of the Fraser government, all of us, the whole country,” Shack told me. “It was the biggest landslide and victory, and Fraser’s political capital, the way they talk about it these days, he could have done anything. But he didn’t. Because he was a mercantilist basically. He wasn’t a free marketeer… The Fraser government was a profound disappointment.”

The dries’ model of criticising their own side from the backbenches is not a familiar one to modern observers of Australian politics, but it has a long tradition in the Westminster system of government. It meant that, as the Australian political scientist Patrick O’Brien put it in his book The Liberals (1985), “given the interventionism of the coalition government in economic matters, the dries, and not the Labor Party which also advocated intervention, were the only real parliamentary opposition to the Fraser government.”

Although less has been written about Shack than about Hyde and Carlton since the events, he played a key role in organising the dries tactically and intellectually. Andrew Peacock (who led the Liberals in opposition from 1983-1985 and again in 1989-1990), told Patrick O’Brien in 1984 that Shack was “in fact the brains behind the dries. Many assume the brains behind the dries was John Hyde. The brains behind the dries was Peter Shack who works with me in my office.”

In his book, Dry: In Defence of Economic Freedom, John Hyde recalls that in the early 1980s, as the dries started to become a recognisable and expanded group of backbenchers, they “did not have the capacity to remain on top of the whole range of issues and were at an inherent disadvantage reacting to them as they arose. Peter Shack suggested… that we should concentrate on selected issues to demonstrate underlying principles.”

The main issue Shack would tackle was the Two Airlines Agreement, the policy of insulating Ansett Airlines and the federal government-owned Trans Australia Airlines from any competitor companies which Fraser had renewed. With characteristic modesty, Shack later wrote: “I have read that public policy reform can sometimes take up to three decades: 30-odd years, to inform, educate and carry public opinion; 30 years to expose and overcome entrenched vested and privileged interests.” In fact, he had lived this. Shack and the dries were the main agitators seeking to undermine the protectionist Two Airlines Agreement. They started talking about it in the late 1970s, but it was not dismantled until the early 1990s (some would argue that elements of it continue to this day).

Although his maiden speech had mentioned some of those issues that would bind the dries together, a large part of it was concerned with another issue that was important to Shack and which he thought the country was missing: leadership. He believed that leadership would be “an issue of the greatest fundamental importance as this country moves from the decade of the 1970s into the 1980s.” (Interestingly for modern readers, given the decades-long decline in the share of the primary vote going to Australia’s major parties, Shack also argued that the results of the 1977 election showed “the urgency of [voters’] desperation [for leadership] reflected in the voting shifts away from the major political parties, the two major potential sources of leadership in this land.”)

It is worth quoting at length from his maiden speech, showing the importance that Shack placed on good leadership.

I believe it is an issue which goes beyond policy, and the mandate that can be found for that policy in election results. That something of which I speak I believe to be found deep in the mood of the nation and the feeling of the people. One senses it in the community, in the air almost. One certainly discovers it from talking to everyday, average Australians the country over… the yearning and the longing of the nation – the silent but overwhelming cry of the people for national leadership. We must recognise that there has been in our society over recent years a crisis of confidence in our political system. The mood of the nation is for stability, security and certainty. I believe the feeling of the people to be for social harmony, political respect, parliamentary peace, electoral normality and national unity. This country needs leadership that is strong, direct and purposeful, yet fair and compassionate; leadership that is morally and politically incorrupt and incorruptible; leadership that recognises and holds up high, above all else, the personal freedom of individual men and women; that puts people first, rejecting any notion of subservience to the State; leadership that recognises personal choice, initiative, enterprise and energy; leadership that withdraws from the nuts and bolts of everyday life decision-making and instead provides leadership – just that, leadership – which points the way by example and by deed and action.

Over the next 15 years of his parliamentary career, Shack would provide this kind of leadership and, through the dries, try to steer the Liberal Party towards being the political party willing to leave cronyism and special favours for special interests behind and deliver for ordinary Australians.

1 Pitt the Younger and Winston Churchill, fall into this category, as would Malcolm Fraser and Paul Keating.

2 I am very grateful that Peter Shack agreed to do some interviews with me, parts of which are quoted in this piece and enable me to make some contribution to the public record of the dries.

3 Carlton will be the subject of the next article in this series.