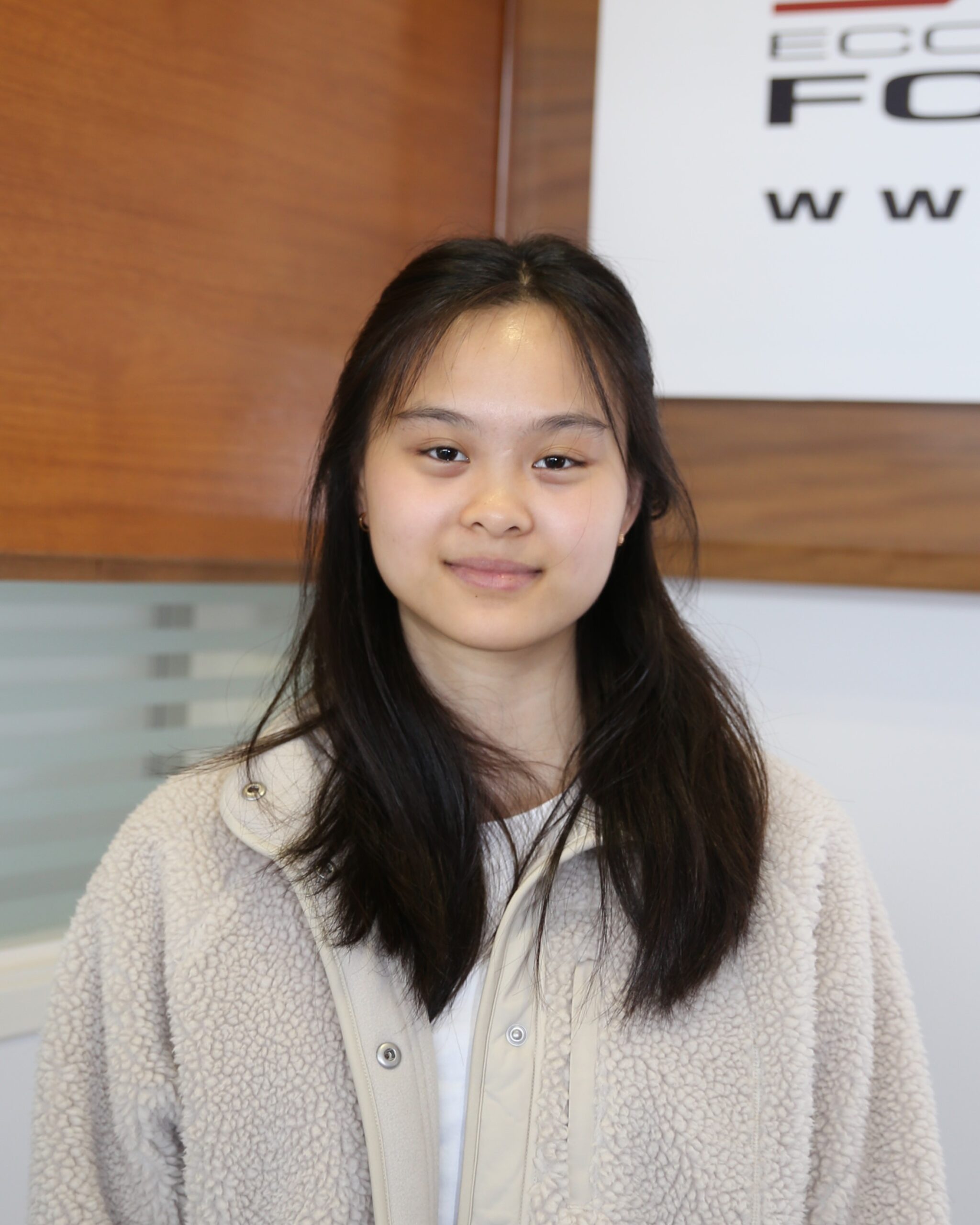

When I think back to my 47 days spent in the Land of Liberty (and “The Greatest Nation in the World”, as proclaimed by the Americans), one word comes to mind: unforgettable.

Our trip began in the picturesque state of Vermont, nestled deep within the mountains. At the Friedmans’ beautiful summer estate, surrounded by painterly skies and mountains, our days were spent in passionate discussion of Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom and Free to Choose, coupled with explorations of Hayek’s political philosophy. Under the guidance of Stephen Miller—using nothing less than the Socratic method of discussion—rich conversation flourished around the connections between economic and political freedom, the role of government, and the responsibility of individuals in shaping markets and fostering equality.

A particularly striking insight arose as we debated whether political instability could, paradoxically, spur entrepreneurship. Drawing on examples from Guatemala, Vietnam, and Indonesia, we examined how economic creativity often blossoms from necessity—especially when social safety nets and formal employment fall short. Trade liberalisation was another key focus, emphasising its contribution to reducing global poverty—but also its limits when paired with monopolistic practices enabled by government subsidies or regulatory capture. These conversations honed my appreciation for free-market principles and the risks of protectionism, solidifying a core belief: limited government fosters vibrant innovation.

Too quickly, we waved bittersweet goodbyes to our newfound friends, as we were whisked away to AIER’s fairytale castle at Great Barrington. Encircled once again by towering trees, open fields, rolling hills, and a rather-feared mama bear and her cub, our first week ended with an interesting and profound seminar about alternative governance. Through a fascinating case study of 18th-century pirate ships, we explored how criminal organisations formed stable systems in the absence of state intervention. Prompting a re-examination of the Prisoner’s Dilemma and the concept of opportunism—the idea that individuals, when left unchecked, will often act in self-interest—it reinforced a notable and fascinating notion: order can arise from voluntary, decentralised cooperation. Through these radical examples, my understanding of governance evolved from initially, a rigid, top-down mechanism to a structure that stems from shared values, mutual benefit, and well-aligned incentives.

Similarly, conversations around social versus distributive justice challenged me to think critically about fairness. While I resonated with Hayek’s view that income should be earned through serving others in voluntary exchange, I also grappled with Rawls’ argument that justice must ensure equality of opportunity, not just outcomes. This tension was echoed in debates on affirmative action—whether such policies are a necessary correction of historic injustice or a flawed solution that risks creating new inequities.

These discussions also encouraged me to reflect on the role of government in enabling entrepreneurship—especially back home in Western Australia. I was reminded of the Centre for Entrepreneurial Research and Innovation’s (CERI) mission to empower individuals to take ownership of their ideas and contribute to a thriving innovation ecosystem. From our analysis of grassroots entrepreneurship in countries with minimal institutional support, I came to better appreciate that governments don’t always need to intervene—they often just need to step aside. Supporting open, free markets with little to no barriers to entry, and aligning incentives with entrepreneurial risk-taking are real policy levers that can drive innovation. I now carry a stronger conviction in CERI’s pillars of economic freedom, education, and community-building, and a clearer vision of what meaningful support for startups looks like.

Finally, I can’t forget the people. As much as this entire experience was characterised by a wealth of newfound knowledge, what made this trip truly unforgettable were all the unique humans I crossed paths with. From doubling over in laughter during 3-minute-positions as we attempted to pitch extremely radical and undeniably inhumane economic policies with straight faces, intense debates on the perceived necessity and actual utility of enormous billboards in America’s countrysides, sprinting up and down hills and towards lakes, late-night camps and conversations in the library downstairs, to tick-checks, grocery runs, chasing sunsets, hikes, cooking, dancing in the kitchen, long, long walks filled with deep, authentic conversation, roping unassuming interns into late-night baking, cornhole, barbeques, wiffleball, wing challenges, Bogies, being crammed into the back of cars, sharing a bathroom with twelve other humans, multi-hour car rides filled with more karaoke, lunch hypotheticals, and so much more – my time in the States has been an ultimate reminder of a simple truth: time spent loving people is never wasted.

No amount of material wealth could ever compare to the lifelong friendships I’ve made and the beautiful, precious memories, experiences, and conversations I’ve been able to share and have. My life is infinitely richer because of it, and I truly would never trade it for anything else in the world.

Six weeks in the States? Truly an unforgettable trip of a lifetime.