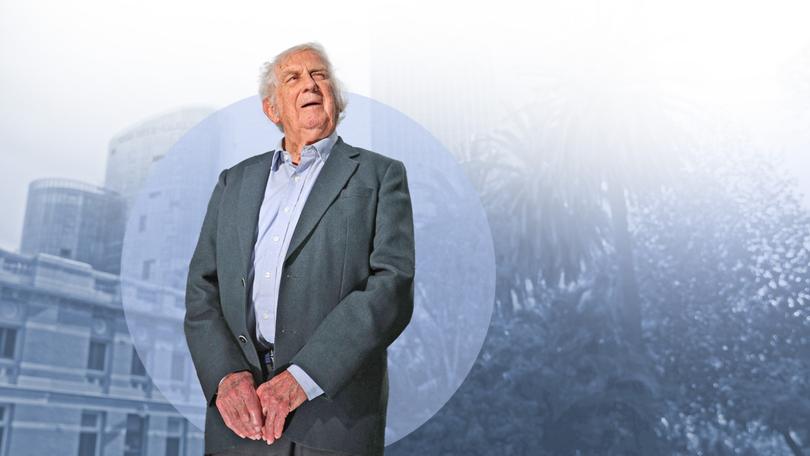

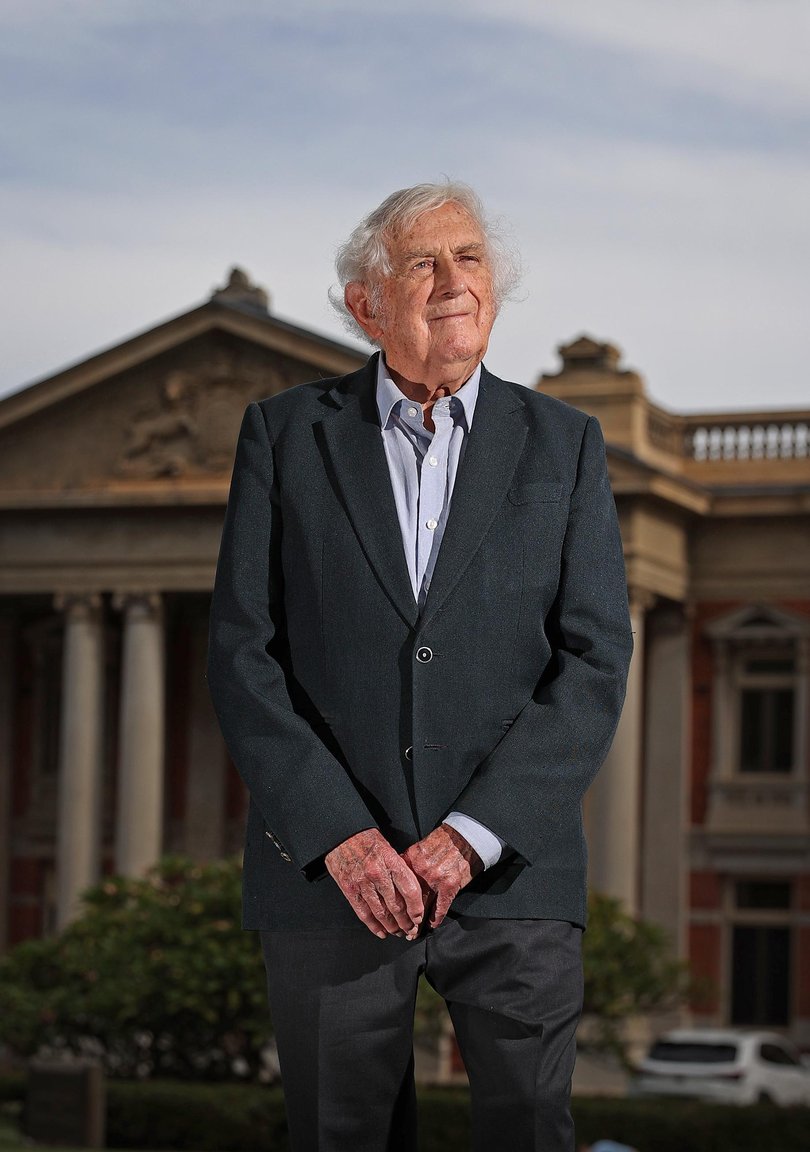

Mannkal was recently the host of noted Australian ‘living legend’ Professor Geoffrey Blainey AC, FAHA, FASSA. Below is a series of videos of the event in which Professor Blainey was the keynote address as well as a series of articles written in the wake of his speech. Mannkal Economic Education Foundation was honoured to receive Professor Blainey attendance at our annual Future Leaders Event.

BEN HARVEY: Politicians could learn a thing or two from listening to Australian historian Geoffrey Blainey

Ben Harvey THE NIGHTLY 4 MIN READ 11 APR 2025

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

“History is not a burden on the memory but an illumination of the soul.”

“A generation which ignores history has no past and no future.”

“History is a vast early warning system.”

There is no shortage of quotable quotes about the importance of appreciating the past.

Geoffrey Blainey would know most of them off by heart.

At the age of 95, Australia’s pre-eminent historian has lived a fair portion of his favourite subject.

Through works such as The Tyranny of Distance, Triumph of the Nomads and The Story of Australia’s People, Blainey has pinpointed Australia’s place in the world at different times.

A recent keynote address he delivered in Perth suggests the custodian and curator of this country’s historical record is now less certain about Australia’s place in the swirl of geopolitics.

If he is sure of anything, it’s the need for Australian leaders to understand they cannot go it alone.

“Our history tells us something very simple,” he told the Mannkal Economic Education Foundation event.

“We, whether we like it or not, must have an ally. If we’re going to have an ally, we have to pull our weight.

“At the moment, Australia’s defences are not very strong. Kim Beazley . . . said quite recently that Australia’s defences are in an unenviable position, and I respect his remarks.”

Blainey has never been one for shrill outbursts and his speech was delivered in the sober language befitting a storied academic.

Even then, his thoughts were sobering.

“People keep on asking a question that’s so difficult to answer. Will there be another world war?

“The news in Ukraine and the news in the Middle East is often disturbing, and quite understandably, so many people, not only in Australia, but in most countries of the world, wonder if this is a precursor to a third world war.

“I’m inclined to think it is not, but one can’t be sure.”

Mr Blainey noted there had been two trigger points for a third world conflict — the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 and Russia’s defeat in Afghanistan in 1989.

“I think of those events and they have some similarity to the situation facing us today,” he said.

“We just can’t be sure.”

Blainey was speaking well before Donald Trump let loose his dogs of trade war. This week’s tariff roller-coaster ride made the following observation about America being guided by self-interest even more prescient.

“When it came Christmas Day, 1941, Mr (John) Curtin said ‘on behalf of Australia, I call on the United States to be our help, rather than Britain in the crisis we face’,” Mr Blainey said.

“We like to think, and we’re often told, that Mr Curtin’s message was heeded; we invited the United States to defend us, and they came.

“It’s not true. We didn’t have that power. The United States had already arrived … nine days before Mr Curtin wrote that plea for help.

“A United States small fleet arrived in Brisbane and began to unload its cargo. We didn’t bring the United States here. We didn’t say ‘please help us’ and they came.

“They came because, sensibly, they realised they needed a forward base, a launching pad from which eventually they can begin to recapture all the islands taken over by the Japanese.

“It’s so important that we remember our history accurately. We didn’t have the power to bring the United States here.

“They came here sensibly to suit, quite rightly, their own interests and ours.”

Mr Blainey warned that even the strongest alliances were tested by the vagaries of politics and economics.

“We should realise that we can in a crisis ask for help from our greatest ally at present, the United States, but it might not be able to help us at the time when the help is needed,” he said.

“A nation needs to be able to defend itself if it’s impossible to get help from an ally at the time it’s needed.”

He ended his speech with an unexpected defence of Donald Trump.

“This has to be said about Mr Trump, that in his first presidency, despite all the statements he made, he was very successful in military affairs,” Mr Blainey said.

“I think that we shouldn’t be too hard on the strange statements he’s been making.

“One remarkable thing has happened which people thought was impossible the day he entered the White House this year, they thought it was impossible that Europe would pull its own weight in defending itself.

“And here, almost miraculously, it looks as though France and Germany and Britain and the main European countries will decide for the first time in three quarters of a century that they will try to pull their weight in defending themselves against Russia, or, if necessary, against China.

“Despite all the strange words that come from him this, if it happens, will be an astonishing achievement.”

Australian politicians searching for a way forward in the new realpolitik of international diplomacy would do well to find a copy of Blainey’s address, if only to remind themselves that while history doesn’t always repeat itself, it has a tendency to rhyme.

This article first appeared in The Nightly here.

We were better prepared for war in 1914 than we are now

From squandering money on over-paid generals to handing over the Port of Darwin, Australia – one of the world’s oldest continuing democracies – is not ready to defend itself. We should all be asking why.

GEOFFREY BLAINEY April 19, 2025

Our nation is not ready to defend itself at this time when a third world war is widely feared. Our military strength has declined just when the danger has increased. Australia was better prepared for the outbreak of World War I in 1914 than it is now prepared for almost any kind of international war.

In 1914 our nation held just under five million people, and if their leaders miraculously were alive today they would be astonished that we – with more than five times as many people – field armed forces so inadequate. Yet this is probably the world’s most perilous time since the end of the Cold War in 1990.

In 1914 a mass of Australian boys and young men had already received some military training: such training was compulsory. In contrast our armed forces today have trouble in recruiting volunteers. The percentage of the male population with any kind of military training is tiny compared with the situation in 1914. At that time most citizens and the major political parties emphasised the need for a strong army and navy.

They were willing to pay for the most expensive item in the list of the world’s major weapons – the massive dreadnought battleship. Australia even placed an order for a fast dreadnought: built in Scotland, it was christened HMAS Australia. Most maritime nations could not afford even one such ship.

My calculation is that Australia had invested, in proportion to population, more money in buying a major warship than did most of the world’s naval powers. We were more adventurous than France, Russia, Italy and Austria-Hungary. What excitement when HMAS Australia – the most powerfulship in the southern hemisphere – steamed into Sydney Harbour on October 6, 1913.

A year later it led a force that captured the German harbour and wireless station at Rabaul in the present Papua New Guinea.

Nothing to supply our war machine

Australia in other ways was more prepared in the era of iron and steel than it is today. On the eve of World War I our first steelworks were busy at the NSW town of Lithgow, while nearby stood the small-arms factory that manufactured rifles, pistols, bayonets and ammunition. It was to employ 6000 people – mostly women – in World War II: today, however, a modern version of Lithgow, ready to supply our war machine, does not even exist.

Darwin is the star harbour on our northern coast and potentially crucial for our armed forces and perhaps one day for America’s too. A leading Chinese commercial and logistics organisation must have been amazed that it acquired the right in 2015 to operate there for 99 years. What a prize! Beijing surely would not dream of allowing the US, Australia or Japan to gain control of a strategic harbour on a vital stretch of China’s coast.

The decision was made by the Northern Territory government in return for a lump sum of money. But should a minor branch of the nation’s political system – not even a state – be allowed to make such a strategic decision? At the time the NT government urgently needed the money. Moreover, the Chinese firm – with Australian staff – has since conducted a loss-making operation that otherwise would have been conducted annually by the NT government at a loss. Inside the same harbour since January 2022 an American firm has been spending at least $270m on gasoline storage for its nation’s needs. At East Arm, not far away, is a base for our own navy’s patrol boats.

Not up to the challenge of China

On Darwin’s future an emphatic warning has just been published by three experts who argue that our defence system is full of holes and patches. Peter Jennings, Michael Shoebridge and Marcus Hellyer are Australian strategic experts. Published by the Institute of Public Affairs under the title of No Higher Priority, their book warns in its first sentence: “Australia is facing its most challenging security environment since the Second World War.” The main challenger is China, but the Albanese government so far is not up to the challenge.

No Higher Priority makes the patient comment that our Defence Department refuses to admit that it “mishandled the issue”. When Anthony Albanese in November 2023 discussed the possibility of forthwith cancelling the Chinese lease of the port, his department advised him to take no action. He himself was content to do nothing . As it was, the Prime Minister’s announcement of election day postponed the matter. The authors conclude that Albanese wished “to avoid a difficult conversation with Beijing”. The evidence suggests that he overall hoped to remain a favoured acquaintance or even a friend of President Xi Jinping. Yet the Chinese know that their presence in Darwin will prevent Australia’s allies from making full use of it.

For the Chinese at the moment, Darwin is not yet as valuable as Taiwan. That island guards one of the world’s most important shipping lanes. It is the hub of the most sophisticated semiconductor factories in the world.

Xi has announced that one day Taiwan will fall into his hands. According to various experts the likelihood of war will continue to grow. They add that such a war, if it involves China versus the US and Japan, could be “horrendous”. One of Japan’s duties might be to provide the hospital ships if a sea battle or blockade occurs.

Who is to blame?

Are our ever-changing political leaders or the heads of our armed forces or the platoons of Canberra bureaucrats mostly to blame for our military weaknesses? Australia is one of the oldest continuous democracies in the world, and therefore we as citizens and voters have also to share the blame.

The three strategy experts admit that many mistakes have been made by Canberra. A too-frequent mistake is a failure to tackle problems that can easily be solved.

One simple recommendation is to build up reserves of transport fuel on our shores so fighter aircraft can continue to fly and warships continue to ply even if our overseas supply lines have been threatened or severed by China or another antagonist.

Three of our remote air bases each have reserves of aviation fuel that would last only about 10 days “for a single squadron of aircraft flying combat missions”. One such West Australian base is at Learmonth, where a fresh supply of aviation fuel from Perth requires truck journeys of 1700km.

Meanwhile, the drone is an urgently needed weapon. Oleksandra Molloy, in her Australian Army paper called Drones in Modern Warfare, has plucked lessons from Ukraine where drones in mid-air shocked the Russian invaders and even sank some of their ships seemingly safe in the Black Sea.

All in all, the latest drones “are becoming stealthier, speedier, smaller, more lethal and easily operable”. In the Middle East the drones and short-distance missiles sometimes serve as a land-based navy, and the terrorist group known as the Houthi occupies shores near the Red Sea and destroys or endangers ships on one of the world’s main shipping routes.

One US admiral declares that his nation has not fought such unexpected sea battles since World War II.

Squandered on generals

The three experts make 36 recommendations, each calling for immediate action. For example, money had been squandered by the boom in well-paid Australian generals, their numbers having doubled in the past 20 years: “Defence suffers from way too many chiefs and not enough Indians.” We are told that Britain, by contrast, has fewer generals and many more privates. The “Canberra bubble” – to use their phrase – has to be pricked.

Likewise, closer relations with India and Indonesia and special relations with PNG are viewed as important. It is also recommended that our alliance with the US would also be tightened if 16,000 US marines were stationed in northern Australia, primarily in Darwin,.

When the voice referendum was held in 2023, Albanese made the staggering decision to give the nation’s Aboriginal population a grip on political power denied to the other 97 per cent of the citizens.

This minority, worthy as it is, would gain the right to consider any major proposal – and how it might affect Aboriginal people – before parliament or the federal cabinet could reach a final decision.

In a grave international crisis, a decision of whether to wage war usually has to be reached by the nation’s leaders with all speed. There is little sign that Albanese devoted thought to this challenge to true democracy.

Indeed, the impressive Aboriginal leaders – Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Nyunggai Warren Mundine – believe firmly in the nation’s longstanding system of democracy.

Other Aboriginal leaders believe that Australian governments totally lack legitimacy. Such a belief, if affirmed publicly, is virtually an invitation for a foreign power to interfere; it is also a temptation for certain Aboriginal voices to exploit an international crisis as a bargaining opportunity. In so behaving they would have the backing of many academics.

There arrived an opportunity in 2024 – and again when election day was finally announced – for the Albanese government to allocate far more money for defence. Richard Marles as Defence Minister and as Albanese’s loyal deputy wanted more, but he probably pleaded in vain. No doubt, amid the tsunami of welfare grants, the response to him by Albanese was predictable: where will we find the money for defence? But if Labor does not gain an outright victory in the coming election and has to rely on the Greens, its defence policy will wobble. Australia might have to abandon or moderate its present policy of buying nuclear-powered submarines. Even the US alliance could be in jeopardy.

The fact remains that Albanese was a failure in sponsoring the voice referendum. He eagerly spoke of uniting the nation but he divided it. The Uluru Statement from the Heart made valid complaints about the treatment of Indigenous Australian – for example, “our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers” – but interspersed these complaints with accusations that were dubious.

All the major universities fully supported Albanese but they failed to add that their own research contradicted some of his views.

Visiting Arnhem Land soon after he was elected, Albanese must have learned that most Aboriginal people had no faith in their own ancient religion, yet their clamour for permanent political powers was primarily based on that religion. The national census every five years proved that the overwhelming majority of Indigenous people, especially in the outback, were Christian. The Prime Minister’s advisers surely had assured him that the ancient Aboriginal religion based on close affinity to the land had few real believers.

Likewise Albanese, before the referendum, did not tell voters that Aboriginal people now owned more than 54 per cent of Australian soil and that he hoped that eventually they should own far more.

Did the Coalition go far enough?

Admittedly in recent years our defences had been temporarily resuscitated. The signing of AUKUS by the Morrison government in 2021, and the promise of nuclear-powered submarines arriving years later, offer us long-term hope. Even the Labor Party, then in opposition, instantly approved the deal.

But years before the first nuclear-powered submarines reach Australia, numerous less-expensive weapons of defence and attack are needed. Plans for specialist ships and aircraft have been devised and approved, but in 2024 the Albanese government decided to prune its more immediate defence needs. In the past decade the Liberals have mostly given a much higher priority than Labor to defence. This week, Peter Dutton affirmed that priority, but did he go far enough?

And now US President Donald Trump’s speeches and actions have added another fear, though isn’t it too early to blame Trump entirely for the economic mayhem and the sudden slump in the world’s financial confidence? After all, he has probably forced the main European nations to take far more responsibility for their own defence – and for Ukraine’s too. If so, he has achieved in his unpredictable way what could not be achieved by Barack Obama’s oratory, Joe Biden’s sad speechlessness and Vladimir Putin’s aggression.

It is not an easy time to be our nation’s leader. Albanese is entitled to feel quietly proud that, coming from a relatively humble background, he was elected Prime Minister. He is entitled to feel elevated if President Xi of China thinks well of him. But Albanese does not accord even a middling priority to what should be the leader’s first duty – defending the nation in turbulent times. He trusts that defence will not be a major election topic.

For at least seven years, however, China has been provocative on sea and land, and one of its countless gestures of defiance was to send, early in 2025, war vessels far into Australian territorial seas without even notifying Canberra.

Albanese believes that if Australia is in peril he will summon the US for immediate help. Yet in some situations the US, with all the goodwill in the world, will be unable to help us at once or unable to help us at all. The case is almost overwhelming that Australia first has to help itself. Even talented scholars who believe we should not be the firm ally of even the US or China are convinced that we should vigorously re-arm.

In the present international situation, a strong defence is vital. The voters are entitled to their say.

This article first appeared in The Australian here.

Australia was ill-prepared for war in 1941. In 2025, we’re making the same grave mistake

Anthony Albanese admits there is an international crisis in nearby Asia and the South China Sea. But he then shuts his eyes.

GEOFFREY BLAINEY April 25, 2025

Australia is not prepared for a war or a half-war near its shores. Anthony Albanese has no wish to discuss this matter seriously: here is a failure of leadership. He admits there is an international crisis in nearby Asia and the South China Sea. But he then shuts his eyes.

Surely we can learn – and he can learn – from the crisis Australia faced in World War II. That crisis, at its depth, was not only alarming for the government in Canberra but must have created fear around the typical dinner table and workplace smoko.

Events early in World War II seemed far away from Australia, especially in 1939. In the following year Adolf Hitler and his forces captured Belgium and Holland, Denmark and Norway. In France the Maginot Line, perhaps the strongest single fortification so far built in the history of Europe, was believed to be the answer to Hitler. But Hitler’s armed forces bypassed it. Within weeks they conquered France. The Battle for Britain, now fought in the air, was seen by many as the prelude to an effective German invasion of that island.

In Australia daily life and leisure went on as normal. In Melbourne in September 1940, at the age of 10, I and my oldest brother were taken to our first football grand final, and there we were a tiny part of a huge crowd seemingly unaffected by the momentous fact that France – our own second most important ally – had recently been trounced. France’s vast global empire was already flung open to invaders. The French colony of New Caledonia, so vulnerable, was only a short voyage east of Brisbane.

In some activities Australia was adventurous in preparing for a war that might approach its unguarded coastline. Essington Lewis, the head of BHP, after touring Japan in 1934, decided its industries were quietly preparing for a major war. Eventually he set up the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation at Port Melbourne where a simple flying machine called the Wirraway was mass-produced. A training aircraft of Californian design, it was the first step in plans to build a faster plane, but the next step was taken only after the Japanese had entered the war.

In January 1941, Australia’s war cabinet learnt that Japan had made its first Mitsubishi Zero, a fighter capable of reaching 300 miles an hour: that was at least 100 miles faster than the Wirraway. The cabinet, however, was privately assured by Britain that Japan would own few such aircraft. Therefore the Wirraway would “put up quite a good show” against the typical Japanese flying-rattletrap, for the Japanese were dismissed as not “air-minded”. Such advice proved to be suicidal for many of our young wartime pilots who had to confront a Zero in aerial combat.

Would Singapore, the British naval base, be equal to the task if war erupted? General Thomas Blamey, the experienced head of our army, decided that Singapore was not in danger of a major attack. A month before the devastating Japanese naval raid on Pearl Harbor, Blamey thought so poorly of the Japanese army that he recommended that all Australian soldiers then training in Singapore’s hinterland should join their comrades in North Africa and the Middle East. There, under the same commander, they could fight the powerful German forces. Fortunately his advice was not taken. Returning to Australia he so advised the government.

The general also noticed people on the home front were incredibly complacent. After attending a crowded racecourse in Melbourne and presenting the cup, he intimated that the throng of spectators resembled a herd of gazelles grazing on the edge of a danger-filled jungle. He knew, however, that intense effort was now directed to the production of munitions in the industrial suburbs.

RG Menzies, the prime minister from 1939 to 1941, had spent weeks in London in the hope of persuading Winston Churchill to reinforce Singapore. Churchill, understandably, believed the key theatre of the war was Europe where Britain, alone of the great powers, stood up to Hitler. For crucial months Churchill’s only allies were Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Looking to the far sides of the world he did not predict Japan’s eagerness to acquire new sources of oil. In the Dutch East Indies and British Burma, valuable oilfields were just waiting to be seized by the Japanese.

Japan, possessing so many aircraft carriers – in short, the world’s largest fleet of swimming islands – first had to cripple America’s great naval base close to Honolulu. Its devastating attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, opened up the Pacific Ocean to a timetable of invasions. On December 8, Japanese forces began to invade British Malaya. British reinforcements almost miraculously had just reached Singapore. The warships Repulse and Prince of Wales had not long arrived – loud was the cheering on December 2. A few days later, without the protection of aircraft, they steamed north. Suddenly, Japanese dive bombers appeared: they flew from the present Vietnam, being the former French Indo-China, and sank the two warships.

Many Australians, on hearing the news, displayed shock and a sense of desperation. According to the American consul in Adelaide, the public mood was “the closest to actual panic that I have ever seen”. The fear was contagious that Australia’s northern ports might soon be crippled by Japanese submarines or bombers.

During December 1941 the Japanese invaded The Philippines, Hong Kong (it surrendered on Christmas Day), Malaya, Burma, the Dutch East Indies, Portuguese Timor and a scattering of strategic islands in the western Pacific. The port of Rabaul in the present PNG even fell to the Japanese before Darwin was bombed. The speed of this chain of invasions had almost no parallel in military history.

Meanwhile, a Japanese army fought its way south towards Singapore. British, Indian and Australian soldiers defending Malaya were in retreat. They lacked the protective armour provided by tanks. They lacked support from the air. Though they far outnumbered the Japanese their morale was not impressive: sometimes they were outwitted by Japanese soldiers riding bicycles. On February 15, 1942, Singapore surrendered. To Churchill it was “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”.

Today Donald Trump is daily reviled by many critics because he is seen as making mistaken decisions. The strain on a leader in a time of national peril was just as visible in Churchill. He failed to predict the Japanese invasions and their stunning success, though in the end he was rightly enthroned as one of the three or four main creators of the decisive Allied victory in World War II. Moreover – wisely it now seems – he resolved that he must support his newish ally, the embattled Soviet Union, and he presented it with more than 300 fast aircraft when such a gift might have helped to save Singapore, though only temporarily

Four days after Singapore was conquered, Darwin was bombed by the Japanese. The most important harbour on the whole northern coast, and busy with the largest number of American and Australian naval vessels so far assembled there, it was bombed twice on February 19, 1942, and again and again in later weeks. There lingered a fear that Australia’s main sea routes might be blocked by Japan. But in the same year the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway Island effectively destroyed the ascendancy of Japan’s navy. Three years later, World War II was finally ended by the two atomic bombs delivered on Japanese cities.

We can now examine the hazardous version of history that tends to shape Albanese’s thinking. He believes he can weaken our nation’s defences but confidently summon the US to mend the defensive fence he himself has broken. In short, does he hope to walk in the footsteps of John Curtin, the new Labor PM who, it is widely believed, persuaded the US to rescue Australia from the Japanese at the end of 1941? This was seen as perhaps his finest achievement, though then he was less than four months in office.

Just after Christmas 1941, when Australia seemed increasingly in peril, Curtin wrote an article for the Melbourne Herald. The nation’s main afternoon newspaper, it was then controlled by Sir Keith Murdoch. In strong language Curtin called on the US to save Australia: “Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.”

Almost forgotten is that Curtin’s article also called for help from Russia, which for the previous six months had been resisting Hitler’s almost bloodthirsty invasion and now was winning the long battle at the city of Stalingrad. Curtin showed brave determination: “We know, too, that Australia can go and Britain can still hold on. We are, therefore, determined that Australia shall not go.”

It is still believed Curtin deserves credit for thus inaugurating the vital US alliance that still survives. Unfortunately, this seems to be a myth. Curtin and his eloquent appeal for military help was not our deliverer from peril. The first American aid had already arrived. On orders from Washington a convoy on its way to The Philippines faced the risk of fierce air attacks and was diverted far south to the safety of Brisbane where it arrived on December 18, 1941. Curtin must have known of its arrival more than a week before he publicly appealed for US help: there is no evidence he tried to deceive the public and claim undue credit for himself. He was honourable: in print he simply blessed what had already happened.

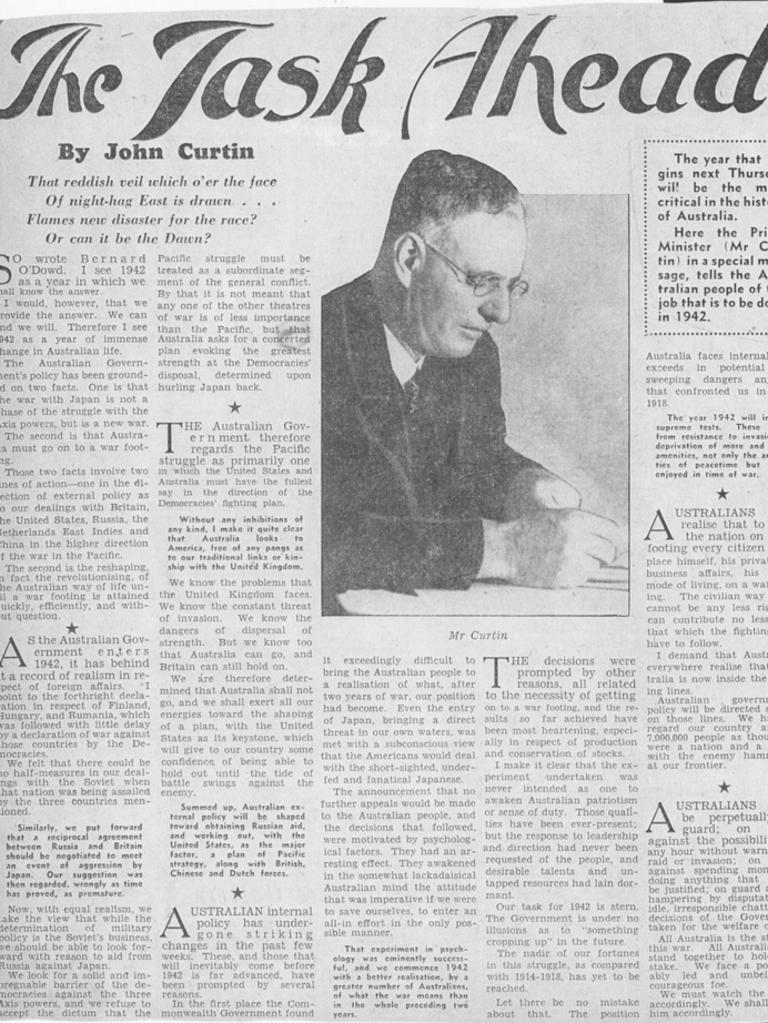

This week I read again his patriotic article, for it formed one of the most influential but misunderstood appeals in our history. He was not clamouring for attention. He started with a verse written by his old Labor comrade, the poet reared on the Victorian goldfields, Bernard O’Dowd:

That reddish veil which o’er the face

Of night-hag East is drawn …

Flames new disaster for the race

Or can it be the dawn?

Curtin was pointing to Japan, which for long had been the nation most Australians, especially politicians, feared the most. Japan was also feared or watched by most Californians. Also known to Curtin was that America came to our aid not primarily because he sought it but because America needed a launching pad and an industrial base from which it could begin the arduous task of recapturing the lands, sea straits and harbours conquered so quickly by the Japanese. Nonetheless, the legend grew that Australia began the tradition of calling for help from America and promptly receiving it. In fact, we have no real entitlement unless we pull our weight.

Albanese should realise that the lesson learnt and taught by Curtin was to defend and rely on ourselves as much as possible. Thousands of Australians died as Japanese prisoners of war or “on active service at sea” because their own nation was not adequately prepared for war. Many are among our war heroes. The Prime Minister has yet to learn that vital truth.

The first American troopships reached Australia in about the middle of February 1942. As children, playing on the sandy beach at Point Lonsdale one afternoon, we saw troopships enter Port Phillip Bay and begin their approach to Melbourne; we could even glimpse the faces of the soldiers who crowded the decks to set eyes on this strange land. Of course we had no idea how lucky was our nation.

When the war finally ended in 1945, Australians knew the nation must populate or perish. Only with a larger population could we provide more airmen, sailors, soldiers and nurses.

For the next third of a century the massive immigration program, initiated by the Chifley Labor government and its enthusiastic minister, Arthur Calwell, was conducted with success. It emphasised social cohesion and loyalty to Australia. Then it gave way to a new ideology that jumped too far in exalting diversity and ethnic loyalties. Eventually we imported considerable numbers of migrants who had no loyalty or scant loyalty to their new nation and sometimes a fierceness towards ancient enemies. They sour the spirit of today’s election campaign.

Geoffrey Blainey is preparing an updated edition of his widely read book The Causes of War, first published in 1973

This article first appeared in The Australian here.