They carry briefs for the general interest against the specific and for freedom against collectivism

In the previous post, we explored how the German economist Wolfgang Kasper helped to put together the Crossroads Group and to provide some of the intellectual heft to the dry movement in the 1980s. He was part of the broader group outside the parliament which made the case for economic reform in the public debate. Much of this work was done through a group of privately funded think tanks which could conduct policy analysis and provide commentary on political and policy debates.

John Hyde has explained the role of think tanks in public policy:

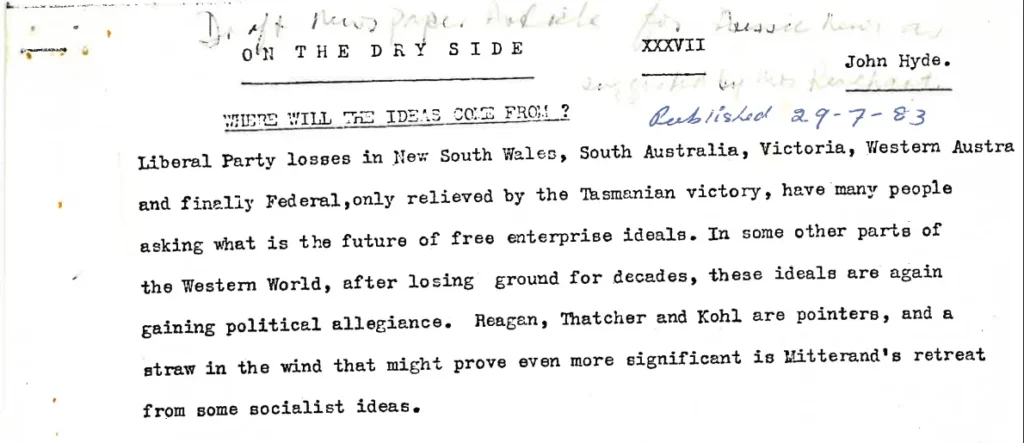

Politicians can and often do lead public opinion, but they only rarely contribute significantly to the ideas with which they do it. Those few who have fancied themselves as intellectuals have generally made poor statesmen, even dangerous ones. The pollie should be able to understand abstractions but original thinking is a specialist’s pastime for which he has neither the time nor temperament. He hears endless criticism but surprisingly few of his critics even try to take a nation-wide view of whatever it is that they are deploring this week. Most of the advice upon public policy coming from the ‘experts at the coal face’ is so dominated by self-interest that it is worse than useless – it is the principal source of corruption of political processes…

Although commonly referred to as ‘think tanks’, there is an aspect to them that is more important to this story than their original thinking: they carry briefs for the general interest against the specific and for freedom against collectivism before the court of public opinion. Although most are academics, the advocates who find their ways to them mark their success not in footnotes but in improved public policy. They are change agents.

There were three main dry-aligned think tanks doing this work in the 1980s.

The Institute of Public Affairs was founded in 1943 by a group of Melbourne businessmen who were concerned about the prospect of Australia’s wartime economic controls being extended into the post-war economy. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the IPA publication Facts provided hard data for political and public debate, while the IPA Review canvassed intellectual contributions from Australia and abroad which could improve domestic policymaking. The IPA hosted conferences, coordinated international speakers, published research papers, and contributed significant policy work, including by largely writing Project Victoria which shaped the agenda of the Kennett government in Victoria from 1992. Part of the role played by the think tanks was to give an intellectual ‘home’ to the dry thinkers. The IPA employed John Stone as a Senior Fellow after he left the Treasury, giving him a platform to contribute to the public debate.

The Centre for Independent Studies (CIS) was founded in 1976 by Greg Lindsay, a schoolteacher who was interested in promoting liberty and free markets. The Australian Financial Review’s economic editor Paddy McGuinness put the think tank on the map in 1978, with a favourable write-up of a CIS conference and provided its address and phone number to readers.

“While denouncing government interference when it suits them, most Australian business interests have a well-established interest in some part of the government assistance and regulatory framework,” McGuinness wrote:

while talking of free enterprise, they are likely to denounce as socialistic proposals for a systematic reduction in government involvement (through tariffs, import restrictions, export incentives, licensing and so on) in the economic system…. A conference last weekend, organised by the Centre for Independent Studies, on ‘What Price Government Intervention?’ presented a refreshing change from the generally uncritical approach to the whole range of government intervention and regulation which is characteristic of Australian policy discussions.

Like the IPA, the CIS hosted seminars and conferences, and published policy papers, and contributed to the public debate. It also provided an intellectual home to dry thinkers, publishing a number of research papers by Wolfgang Kasper, for example, from the 1980s through to his death.

In 1983, after his parliamentary career, John Hyde established the Australian Institute for Public Policy (AIPP), a new think tank based in Western Australia. The AIPP published detailed lists of the spending “cuts that would allow Federal budgets to be balanced without increasing taxes.” This work was partly intended to show “the public and some backbenchers who would never see a Treasury ‘hit list’ that budget cutting was a realistic option.” The AIPP was merged into the IPA in 1991, and John Hyde ran the enlarged IPA for some years thereafter.

Australia’s dry-aligned think tanks used the various forums and tactics available to them to push opinion toward supporting economic reform. As Paul Kelly recalled in The End of Certainty, through the 1980s they became “influential among opinion makers in the media, academic and politics”, the class of ‘intellectuals’ Friedrich Hayek argued it was critical to win over as it decided “what views and opinions are to reach us, which facts are important enough to be told to us and in what form and from what angle they are to be presented.”1

Think tanks continue to play an important role in policymaking and in promoting the ideas and legacy of the dries. The Mannkal Foundation (who the author gratefully thanks for the support to write this series of articles) has done a significant amount of work to keep the dry legacy alive, including by digitising and publishing the John Hyde Archives.

1 Hayek was one of the international speakers to the IPA helped to bring to Australia for a lecture tour in 1976.