This report forms part of the Special Centenary Publication: Government Waste by The Taxpayers Research Foundation Ltd (part of Tax & Super Australia).

By Andrew Pickford and Cian Hussey.

Introduction

The past decade in Western Australia has been a troubling time for those concerned with the nature and scale of government waste. Instances of wasted taxpayer funds, where vast sums of money were committed to nefarious policies and pet-projects, can be found across a range of government departments. In this paper three examples of such waste are provided in Royalties for Regions, the sponsorship of Western Force, and the mismanagement of the Swan River Pedestrian Bridge. Royalties for Regions is the focus as it contains particularly frivolous projects and has come at a substantial cost to taxpayers and resulted in serious complications for the state budget. As such, it will provide the basis of the lessons for policymakers.

1. Royalties for Regions

As a highly urbanised nation, Australia has a small but active rural and regional population. While made up of many enterprising and industrious individuals, there are some who believe getting their “fair share” of the economic bounty can justify waste, the Australian version of “bridges to nowhere”. The National Party in Western Australia fell into this camp. They proudly defended their brainchild, Royalties for Regions (RfR), which explicitly redirects funds to a geographical zone in a process shown to be deeply flawed and described by a leading economic commentator as “formalised pork-barrelling”.

The RfR program was an election platform of the National Party in Western Australia that was intended to assist in developing regional WA. Implemented by the Liberal Party and National Party coalition elected at the 2008 state election, the RfR program hypothecates 25 percent of forecast royalty revenue to be spent on promoting and facilitating “economic, business and social development” in the regions. While some beneficiaries and commentators claim that the program has created benefits for the state, their statements are based on belief and lack both economic rigor and publicly-made assessment of social benefit. The facts, supported by subsequent government audits, indicate that it has been a wasteful use of taxpayer funds, creating a number of direct and indirect negative consequences and contributing to the poor fiscal standing of the state government.

This paper draws upon Public Choice theory, which argues that in democracies concentrated vested interests can prevail over broader and less-organised ones, along with economic analyses to show that both the premise and mechanics of the policy are deeply flawed.

Background

WA is a boom-bust resources state exposed to world markets. Historically, the benefits of resource development have been shared mainly through economic multiplier effects rather than being taxed and redistributed directly. In the late 1990s, concerns were raised that these benefits were not realised by the communities where raw materials are extracted, resulting in calls for increased government funding for regional parts of the state. In the lead up to the 2008 election, the Nationals adopted a policy originally suggested by The Greens to address this apparent issue.

The Nationals sought a balance of power at the election, ensuring that this policy, Royalties for Regions, would be implemented by making it a condition of any coalition to form government. In doing so, the Nationals effectively became a lobby group sitting in parliament, having switched their focus from agriculture to regional WA. While a departure from a responsible approach to governing, this move was not out of character.

The ability to establish the RfR program was essentially an act of political opportunism, but one which may cause long-term problems for the WA Nationals. The decade of fiscal disrepute and pork barrel politics may be popular with small sections of regional Western Australia, but it draws into question the future of regional based representatives to govern for the interest of the state.

Waste and the lack of fiscal restraint in Western Australia should not be blamed on only the WA Nationals. Introduction of the RfR program coincided with a lack of fiscal constraint generally. A number of major infrastructure works along with public sector wage inflation put the government into a problematic fiscal position.

Despite favourable economic conditions, particularly the increasing value of commodities, the viability of the state budget soon deteriorated. Prior to the 2008 election, the Department of Treasury and Finance warned that GST grants and transfer duty revenue would decrease significantly, offsetting increasing revenue from royalties. If the Coalition had heeded this warning they would not have hypothecated funds which, by its definition, would cause an inflexible fiscal position. By ignoring Treasury’s warning and proceeding with the RfR legislation, the government negligently placed the budget under further strain.

Redirection and Redistribution of Tax Revenue

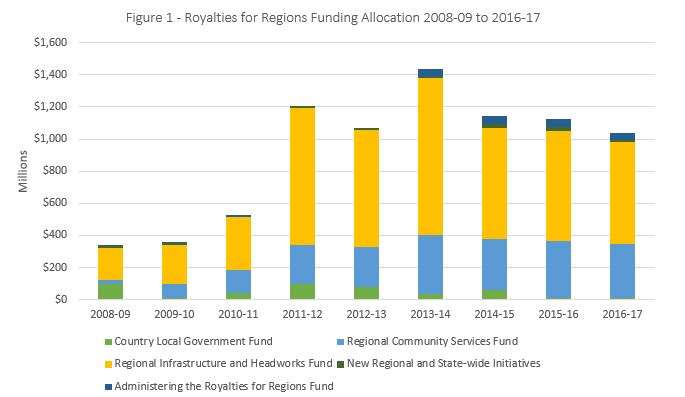

From 2008-09 to 2016-17, the total hypothecated funds from the RfR program was $9.09 billion, with an additional $260 million in interest and refunds. Of the total $9.35 billion, only $620 million was returned to the Consolidated Account. The allocation of this funding over the lifetime of the program can be seen in Figure 1.

Problems with RfR

The WA National Party shamelessly auctioned off its balance of power in exchange for its regional development program. They effectively forced their policy, which had no evidential basis, into legislation and defended the scheme for a decade despite evidence that it was not working as promised. This sort of behaviour is criticised by some Public Choice economists as a practice “dominated by political interests and likely to load costs on the general public”. Given the availability of funds at political whim, it is no surprise that the program facilitated widespread rent-seeking.

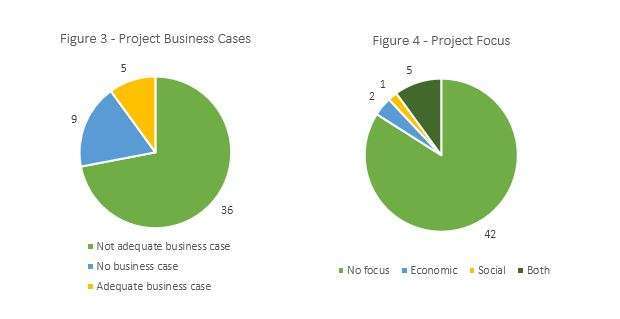

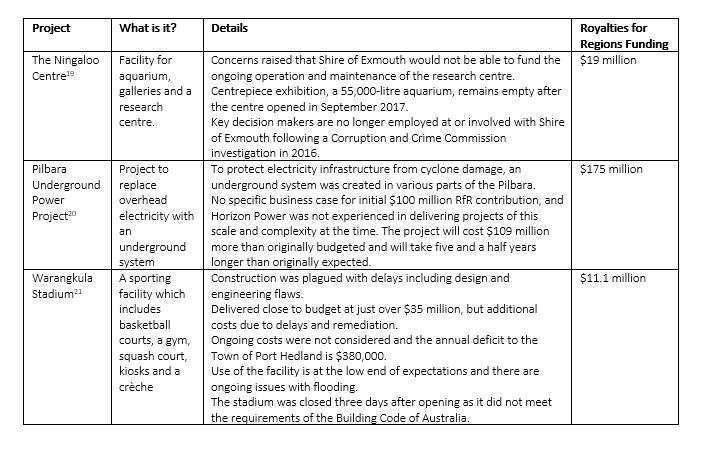

As part of the John Langoulant-led Special Inquiry into Government Programs and Projects, economic consultancy firm ACIL Allen Consulting reviewed a selection of 50 typical RfR projects to assess their social and economic outcomes and the adequacy of their business cases. As can be seen in Figure 3 and Figure 4, these projects largely failed to provide any benefit or be supported by a business case. These poor outcomes are explored in the following section ‘Case Studies’ where some specific projects are considered.

Case Studies

In light of the context and scale of RfR elaborated above, specific case studies grant insight into the abhorrent nature of the program. As discussed previously the premise of RfR is flawed and the examples below are particularly egregious consequences of it.

Issues and Findings

The flawed premise of RfR has translated into poor outcomes for specific projects as illustrated above. In addition, there are a number of practical limitations which arise as a result of the specific way that the program works.

- Arbitrary funding amounts are unlikely to ever match the necessary levels of expenditure, and do not take into consideration economic conditions, affordability, competing government priorities, or the quality of projects under consideration.

- We find that arbitrary percentage limits are not an effective policy setting, and that all funding should be based on a sound business case and rigorous cost-benefit analyses.

- Hypothecating funds hamstrung the fiscal flexibility of the state budget.

- We find that funding should never be hypothecated as it distorts state budgets and removes the role of Treasury in being responsible for expenditure. Hypothecation limits the ability of governments to respond to changing macroeconomic variables, which is particularly important in resource-exporting economies like WA’s.

- Furthermore, legislated hypothecation impacted the GST calculation, forcing the government to borrow from other revenue: “The Grants Commission process causes some tension with Royalties for Regions. Some years, where the GST takes 100 per cent or more of royalties due to the lag, the State borrows money to fund Royalties for Regions”.

- We find that legislating RfR created adverse impacts on other revenue streams, namely the GST share. From a cyclical perspective, the timing impact and lag effect exacerbated the poor policy and its effect on taxpayers.

- Projects often fail to fulfil any social or economic goals and are often presented without an adequate business case.

- We find that RfR lacks processes of accountability and due diligence. In addition, it has been noted that while RfR has successfully delivered infrastructure and services to the regions, their necessity and long-term benefits are uncertain. There is a strong incentive for projects to be approved based on available funds rather than demonstrable need, leading to on-the-run funding decisions.

- Local governments are burdened with the responsibility of maintaining services and infrastructure.

- We find that any commitments to fund infrastructure and services should include an analysis of the levels of recurrent expenditure required to fund such commitments and the ability of local government to meet these obligations.

- Government-led attempts to shape regional growth in slow-growing areas are very likely to fail.

- We find that rhetoric surrounding RfR and its ability to shape the regions were flawed and lacked economic and intellectual rigour. A “build it and they will come” approach to development was pursued, which, according to Daley and Lancy (2014), defies economic principles of development and Australia’s trend of agglomeration economics.

2. $1.5 Million Sponsorship of Western Force

In late 2016 Western Force, the Western Australian rugby team, were struggling to remain financially viable. In a bid to prevent the team from being removed from the Australian Rugby Union (ARU), a hasty agreement was made between the Road Safety Commission (RSC) and the ARU (then-owners of the Force) whereby the RSC would sponsor the team and provide $1.5 million in funding. Such payments, made from the Road Trauma Trust Account, is reserved for supporting “the development and implementation of sustainable projects and one-off community activities related to road safety”. After an initial refusal of the arrangement at the beginning of January 2017, the RSC quickly changed its decision and the arrangement was recommended to and authorised by the Minister by 30 January 2017.

The John Langoulant Special Inquiry mentioned previously discussed the RNU/RSC agreement, noting that: “there are no documents evidencing how or why the Road Safety Commission altered its view over the course of several days… as to the appropriateness of the Western Force sponsorship”; “there was seemingly no assessment of how the proposed arrangement would enhance goals that the Road Safety Commission professed motivated its entry into the arrangement”; and that there was no “cogent explanation… as to why this agreement was entered into in such haste”. The payment was also unprecedented in size; with the next-largest pay out from the Fund being worth approximately $50,000.

3. Swan River Pedestrian Bridge

In 2012 the Western Australian state government announced a new pedestrian bridge to be delivered as part of the broader Perth Stadium project. When the project was announced, it was expected to cost $54 million and be completed by the end of 2016, well ahead of the new stadium which was set to open in 2018. The footbridge became infamous in Western Australia for the headaches it has caused both the Barnett and current McGowan state governments and was eventually opened to the public in July 2018, 18 months late and at a total cost of $91.5 million.

In 2015, only a few months after the initial contracts for the project were signed they were changed as the ‘landing point’ of the bridge had to be moved 19 meters south on one side. This change is estimated to have added between $8 million and $10 million to the total cost of the project and was flagged by the Langoulant Special Inquiry as an avoidable issue that should have been resolved prior to any contracts being signed. In addition to the delays caused by changing the plans and contract, the construction of the steel for the bridge caused significant delays. The bridge was to be constructed in Malaysia and shipped into Perth, with the first shipment expected to be delivered in July 2016. No section of the bridge ever arrived from Malaysia and the McGowan government eventually announced that the bridge would be built in built locally instead. This announcement, made in June 2017, came more than six months after the bridge was supposed to be completed.

Despite its opening in July 2018, the bridge remained unfinished with one journalist noting that there was not proper drainage, surfaces were unfinished, railings were not aligned properly, and dark paint was splattered across white hand rails. According to Main Roads Western Australia, the principle department responsible for the project, work continued at the site into March 2019 to remove construction rock from the river, finish painting the steelwork, and complete a final tidy-up.

Conclusion

In the past decade, examples of misspent taxpayer funds have been rife in Western Australia. Those explored in this paper, from ill-conceived plans to assist a struggling rugby team to blatant pork-barrel politics, highlight some of the most concerning examples where taxpayers’ interests appear to have been forgotten by state governments. Shedding a light on this waste is an important part of keeping government accountable, exposing their mistakes, and providing critical insights to advise current and future leaders.

In particular, the Royalties for Regions program and the economic mismanagement it entails can provide a number of lessons for policymakers:

- Hypothecating revenue prevents governments from allocating funds to areas of greatest need and does not allow Treasury to provide the necessary oversight that is central to responsible governance. RfR functions in exactly this manner, notably preventing the government from reducing state debt as the money is instead allocated to unnecessary projects with little to no oversight.

- When favours are granted to one group at the cost of everyone else, the essential principle that parliaments are responsible to the whole community is disregarded. This should be a paramount concern as it allows for rent-seeking groups to push for programs such as RfR where the wasteful, patron-style form of distributing funds allows for unchecked misallocations of resources; a boondoggle of momentous scale.

- Politicians in boom-bust resource states like Western Australia should never take the current economic situation for granted. When fortunes are prone to fluctuate, governments should seek to prepare for the future. When short-term electoral gains are sought through pork barrel programs, the tough times to come are made all the worse. Excess royalty revenues should be used to pay down debt and create a more sustainable economic environment, to the benefit of the entire community.

In the early 20th century, Australian economist Edward Shann warned that reliance on temporary booms to fund economic activity was not a sustainable practice.[1] This remains true and the Coalition needed not look so far back as Shann to realise this as the Treasury department highlighted shortfalls in revenue before Royalties for Regions was even implemented. Rather than the economic mismanagement and corrupting influence of Royalties for Regions, Western Australia should emulate the “Alberta Advantage” where excess royalty revenues are used to pay down state debt and reduce tax burdens.

While the Western Australian government maintains Royalties for Regions, it normalises the process of political aspirants enriching their particular subgroup to the detriment of the wider community, damaging the long-term health of the state’s economy and maintaining the already-decade-long reputation for mismanagement of taxpayer funds.